Two years ago we were contacted by Dorothy Ramser daughter of Sgt M. I. Dickson. We published the true story she wrote about the experiences of her dad, one of the three British gunners during the battle for Veghel in WW2, also known as ‘Operation Market Garden’. Last year and again this year she offers us a true story which she has written after a lot of research and contact with the descendants of the soldiers.

With regards to the liberation of Eindhoven on 18 September 1944, which is celebrated every year, we like to give you an idea of what went on in the personal lives of the fighters. The perspective of those days is much different from how it is today.

Dorothy adds: “This story is about a pilot in RAF Bomber Command who was killed and buried in Eindhoven along with his crew. Thomas came from my hometown in South Shields. His twin grandsons still live there. I’m in touch with them. Martin and David Purdy. They had no idea until I told them that their grandpa had a grave. They believed his body had never been found. They hope to visit the cemetery next year. ”

Thomas Purdy was born in South Shields, an industrial seaside town in the North East of England on the 28th June 1913 to parents George Lancelot Laidler Purdy, a Colliery Fitter and Elizabeth a housewife.

Young Tom attended Westoe Central School in South Shields. It was an era when much emphasis was placed on reading, writing and arithmetic and discipline.

Then in January 1930 at the age of 16 on completing his secondary school education, Thomas left home to become an apprentice at RAF Halton in Buckinghamshire with a view to gaining qualifications as an RAF mechanic. To be admitted to this prestigious establishment Tom would have had to pass the RAF entrance exam and the medical – as he was a keen sportsman he would have had no problem with this aspect. Indeed he went on to become a talented boxer and won many boxing trophies for the RAF. Great Grandson Jack Thomas Purdy who inherited this boxing skill, is the proud owner of his grandpa’s Wakefield RAF Boxing Trophy Gold medal from 1936 which he treasures.

One of the Boxing Medals won by Thomas – Great Grandson Jack Thomas & Dad, Grandson Martin

He thrived in the RAF and by 1937 Thomas was a pilot sergeant at RAF Driffield and married his sweetheart Ellen in full RAF uniform, in a ceremony in South Shields flanked by his airmen comrades.

Tom & Ellen Purdy 1937

It was not long before a son Ian Thomas was born in 1939. At that time Tom was a Wellington pilot with 9th Squadron at RAF Honington in Suffolk whilst Ellen remained in South Shields looking after their baby. The young couple must have relied on short leaves home from the base to spend time as a family and for Tom to get to know his baby son at the family home in Marsden Street.

In July 1937 his Squadron had the great honour to represent the RAF with their Wellington bombers at the Brussels International Air Show and impressed the spectators with their daring display. They had also met and exchanged wary pleasantries with their Luftwaffe counterparts, not realising that they would be clashing in battle two months later!

On the 1st of September squadron mobilisation was ordered and all aircraft were despatched to dispersal points and put on readiness. The following day the Operations Record book recorded the ominous line “State of War with Germany declared as from 11.00 hours” Britain was once more at war with Germany.

The next day an order came in around noon at the HQ of 9th Squadron for them to join in an attack with 14 of their Wellington bombers on the enemy fleet at the entrance to the Kiel Canal. This was the first raid of the war.

The briefings for all the squadrons involved were unusual for the fact that the King sent them a message of support and encouragement on behalf of the country. The weather was horrendous for the operation but the bombers were nevertheless loaded up with their deadly cargo.

Purdy was selected as Section 4 commander, Flight Lieutenant Peter Grants’, wingman. They were to stick close throughout the raid. It was known because of an earlier reconnaissance flight that day that the renowned enemy battleships the Gneisenau and Scharnhorst were among the German fleet harboured there.

Tom Purdy’s aircraft taxied down the runway and took off at 15:40 and a little after 6 o’clock approached their target of a battleship near the entrance to the Kiel Canal. Tom ran the gauntlet of 2 shore batteries on the North bank of the river blasting concentrations of devastating fire at his plane packed with bombs. Each of the batteries were on the water’s edge and were equipped with 4 anti-aircraft guns each. As well as the battery guns to contend with Tom was under fire from two big battleships and eight cruisers. Their group of Wellingtons was hit three times – bullet and cannon holes peppering the thin skin of the Wellingtons, but Tom pressed on to his objective under the murderous fire and reached their objective – a battleship lying in harbour and his section of bombers all dropped their bombs at the same time and the ship was set on fire. As the bombs dropped the aircraft rose, lighter without its load and they set course for home and away from the cannon fire, always wary of pursuit by Messerschmitts. Two of his Squadrons aircraft were the first to be shot down on the western front. The Squadron claimed one Messerschmitt shot down.

The raid took the Germans by surprise and it was the very first time air raid warnings were sounded in Germany. Tom landed safely at Honington just after 9pm no doubt exhilarated and exhausted, and happy to have survived and I’m sure they were very pleased to be home drinking hot, sweet tea giving their reports after their first time under fire.

A Flight of 9 Squadron’s Wellingtons 1940

At 9’clock in the morning of the 18th December, 9th squadron Wellingtons were moving slowly towards the runways ready to take off in a return attack on the Kiel area in search of battleships.

As the formations entered the Heligoland Bight they were almost immediately met by enemy fighter aircraft. Only one attempted the desperate task of closing in on one of the bomber sections and was immediately shot down by rear gunners. But as the group of bombers approached its objective at Wilhelmshaven, the skies began quickly to fill with German fighters and they soon began to close in and attack the RAF from all directions.

Then, as the bombers came over Wilhelmshaven, they were exposed to the full blast of the anti-aircraft defences. The Germans hoped to force the formations to open out so that their fighters would be able to deal with them individually, and it was after the bombers had completed their task and turned away from their objective on the return journey that the main attack of the enemy fighters swooped in. Casualties on both sides began to mount. The Messerschmitts attacked at great speed trying to sweep the bombers with bullets from stern to stern. The Wellington bombers resisted these tactics by flying wing tip to wing tip whilst under heavy fire from anti-aircraft guns on the ground. Many of the British bombers fell victim to this and plunged to the ground, whilst others fought them off and managed to cross 300 miles of sea with gun turrets out of action and severe damage to the planes.

Two Wellington Pilots

One of these aircraft managed to shoot down 5 enemy planes and although the crew were under attack continuously for nearly 40 minutes and closely followed 60 miles out to sea by German fighters they succeeded in driving them off and bringing their aircraft back safely. This was due to the skill of the gunners and the pilot and to the second pilot who, when two of the gunners were wounded, ran from one gun position to another to meet the attacks from different directions as they happened.

A Wellington Wireless Operator and Rear Gunner

The pilot said later “The enemy attack was sustained and most persistent throughout, and kept all our gunners fully occupied as they used 5 fighter aircraft to attack each bomber. If at any time during the battle we managed to get a 15 second respite from attack we were more than grateful. “

One aircraft had to leave the formation and descend into the sea some distance off the English coast, through a petrol leak caused by gunfire. This aircraft had got severely shot at in the action, all of its guns had been put out of action by shells and machine gun bullets, and the bottom of the front turret had been blown out by shells and set on fire. “My gunner was very prompt with the fire and put it out with his gloved hand. But for him the aircraft would have been well alight within a few seconds. His quick action saved our lives. When the bottom of the gun turret was blown away the gunner (Ronnie Driver) found that his leg was dangling in the air over the water, but his huddled position kept him from falling into the sea.” This young gunner was 18 year old Ronnie Driver, Hollywood actress Minnie Driver’s father who was awarded the DFM for this act of bravery. The pilot landed on the water as near to a trawler as he could so they could be quickly rescued from the freezing sea.

The leader of the formation summed up the battle ”This was in fact the biggest aerial battle up to this time ever fought. At a guess I should think about 80 to 100 aircraft were engaged. We were really greatly outnumbered and out-manoeuvred because of the higher speed of the fighters. Our crews fired shot for shot and most were under fire for the first time”.

Pilots and aircraftmen helped to save the life of one of the gunners. They made a human escalator of their backs to remove him as gently as possible from the aircraft before rushing him to hospital. He had been shot through the thigh and although the bullet had missed both bone and artery, he had lost a great deal of blood on the long and extremely cold flight home. The pilot decided to land at the nearest aerodrome once in British skies. As he landed he was cheered by the waiting pilots, and suddenly a tyre burst and the aircraft swung round in a circle. Both wings were largely in tatters and the fuselage was riddled with bullet holes. One wing had burst into flames. A bullet had torn the sole from the boot of another crew member but he was lucky to escape with a graze and a slight burn

It was a terrifying return journey for the Wellington bombers as Messerschmitts pursued them back across the North Sea. The Wellingtons did not have self-sealing fuel tanks so easily caught fire. 10 Wellingtons were shot down and 2 more were forced to ditch before reaching Britain and 3 more were destroyed in crash landings. Thomas Purdy must have been a skillful flyer as he was able to force land his bomber safely without his undercarriage which ensured he got his wounded crew swift treatment back home.

However, lessons were learnt and the Wellington fuel tanks were quickly modified and guns added on either side of the aircraft. Bomber Command abandoned daylight bombing because of this raid and resorted to night bombing only.

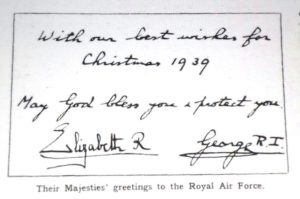

On Christmas Day every officer and man in the Royal Air Force received a Christmas card from the King and Queen, with photographs of their Majesties. The King was shown wearing RAF uniform.

Throughout this time Tom flew on raids and between tours he trained pilots.

Sergeant Thomas Purdy was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal on 24th December 1940. Here is his citation:

“Sergeant Purdy has taken part as Captain of aircraft in most of the important operations undertaken by the squadron since 4th September 1939 and has at all times shown conspicuous gallantry and determination in pressing home his attacks in the face of severe enemy opposition and in adverse weather conditions. His success as a captain of aircraft is no less marked than his skill and determination as a pilot and he has imbued his crew with a team spirit to a marked extent. By his courage, persistent determination, skill and power of leadership, this N.C.O. has at all times set an example deserving of the highest praise.”

Remarks by his Air Officer Commanding:

“Although on one occasion during his first tour of duty his aircraft was extensively damaged during an attack on Wilhelmshaven with necessitated a forced landing without his undercarriage at a strange aerodrome and with a wounded crew, his determination was in no way shaken and he completed his normal tour of duty in an operational unit. After three months employment on the O.T.U. he returned to his original unit as full of vigour and determination as ever and has at all times been an outstanding member of his squadron and sets the very best example to all junior Captains.”

Distinguished Flying Medal

Then in mid 1941 Thomas Purdy transferred from 9th Squadron to 57th Squadron at Feltwell. For a while he was night flying instructor at the base. It wasn’t long before he was back on operational flying with raids to Emden and the industrial Ruhr.

At 5-15pm on the 27th December 1941 Tom took off in his Wellington from Methwold to attack the marshaling yards of Dusseldorf.

Purdy pushed the bomber to 12000ft and left the Suffolk coast at Orfordness lighthouse. The moment the bomber crossed over the Dutch coast they were predictably attacked by enemy flak guns. Once through the flak Tom passed the controls to young 2nd Pilot Max Cronin from New Zealand. Ron Scarlett from Australia kept an eye on their course whilst Jimmy Poulton and Bob Aldous scanned the sky, alert for enemy fighters in the moonlit night. Max kept the Wellington weaving to make it a harder target for the enemy. As the heavily loaded bomber approached Dusseldorf in the Ruhr they could see the sky lit up with searchlights. Heavy flak from the anti-aircraft guns on the ground burst all around them buffeting and jolting the plane vigorously, and terrifying the tense airmen with its loud bangs at close quarters. They could see RAF bombers ahead were already dropping their bombs adding to the cacophony of the night. Thomas Purdy liked to be able to identify his target properly and bombed at 12000ft rather than at the usual 15000ft and as they approached the target Tom took over the controls of the aircraft from Max who went into the astrodome to watch for flak which was intensifying around them as they neared the target. Meanwhile on the approach to the drop zone Ron Scarlett bomb aimer lay down in the nose to be able to identify their target and drop the bombs. The sky was clear and it was easy to see and Ronald Scarlett gave his instructions to Tom in the cockpit to manoeuvre the aircraft over the zone and then called out “Bombs gone!” no doubt provoking a collective sigh of relief and five 500lb and one 1000lb bomb hurtled towards the ground.

Suddenly the cockpit was lit up by searchlights – they’d been ‘coned’ which meant only one thing if they remained within its beam – they’d be shot down or worse blown apart by shellfire. Tom had no intention of sticking around for that to happen and he pushed the Wellingtons nose down in a vertiginous dive with the crew hanging on to anything they could find as they hurtled down 5000ft at great speed. Tom lost the searchlight and at 7000ft levelled the plane out. They were probably feeling huge relief thinking they had escaped danger for the moment when incendiary shells whistled through the bottom of the aircraft and it burst into flames. The badly damaged Wellington lost height as Thomas struggled to control it, all of his experience coming to call as he battled in the night sky with flames gaining ground. He must have known it was hopeless and gave the order for the crew to abandon. Stan Barraclough saw him for the last time hauling back on the control column hoping to give the crew valuable seconds to escape. It was an extremely noble effort to try to save the lives of others. Stan saw Ron Scarlett raise the escape hatch door and jump into the night sky and Stan followed him.

Nobody else jumped out and as he floated downwards he saw the burning aircraft hurtle to the ground and explode on contact. Ronald Scarlett’s parachute was nowhere to be seen.

Stan Barraclough sought refuge in a farmhouse only to find out they were informers and he was quickly taken prisoner and incarcerated in a military prison in Amsterdam. From there he was taken to Dulag Luft and then to Stalag 383 at Hohenfels near Nurenberg where he stayed for the remainder of the war.

The family of Thomas Purdy in South Shields had to wait until 23rd July 1942 until he was officially stated killed in action. His young son was never to know his brave father. It was the same for the devastated family members of Ron in Melbourne, Max in Adelaide and Bob and Jimmy in Britain. It left scars that no medal or memorial could heal.

The crew members are buried in a line together in Woensel Cemetery Eindhoven. Ronald Cave Scarlett’s Mother and family in Australia included this epitaph on his headstone “For God, King and country his duty nobly done”. A fitting and sincere tribute to them all.

Author: Dorothy Ramser

Photographs Copyright: Martin Purdy & Family

On May 26th 1941 Thomas Purdy was co-pilot in Flying B-17 AN530 across the Atantic